A few of these essays need a longer-than-usual introduction, and this one one of them.

Fresh out of college, I worked occasionally as a researcher for the conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth, and through that came to know Cornelia Lauf, who had married him. At the time, Cornelia and her colleague Susan Hapgood were preparing an exhibition of Fluxus-related art, and they hired me to research toys that were contemporary with the Fluxus movement and to acquire them for the exhibition.

Cornelia and Susan also commissioned Rirkrit Tiravanit, a friend and collaborator at the time. He was still working out the ideas that the art critic Nicolas Bourriaud would later call “relational aesthetics” (a bit speciously, imo), and he proposed to have the attendees of the exhibition opening unpack and hang the artworks.

One of the “toys” was a small self-inking stamp that said “!!great!!” — an arbitrary object but one that chimed nicely Fluxus artists’ impulse to take the p*ss out of institutional art culture, so it was included. Someone at the opening used it to stamp all over a piece (by Malevich, as aI recall) that MoMA had loaned for the show, causing a minor crisis.

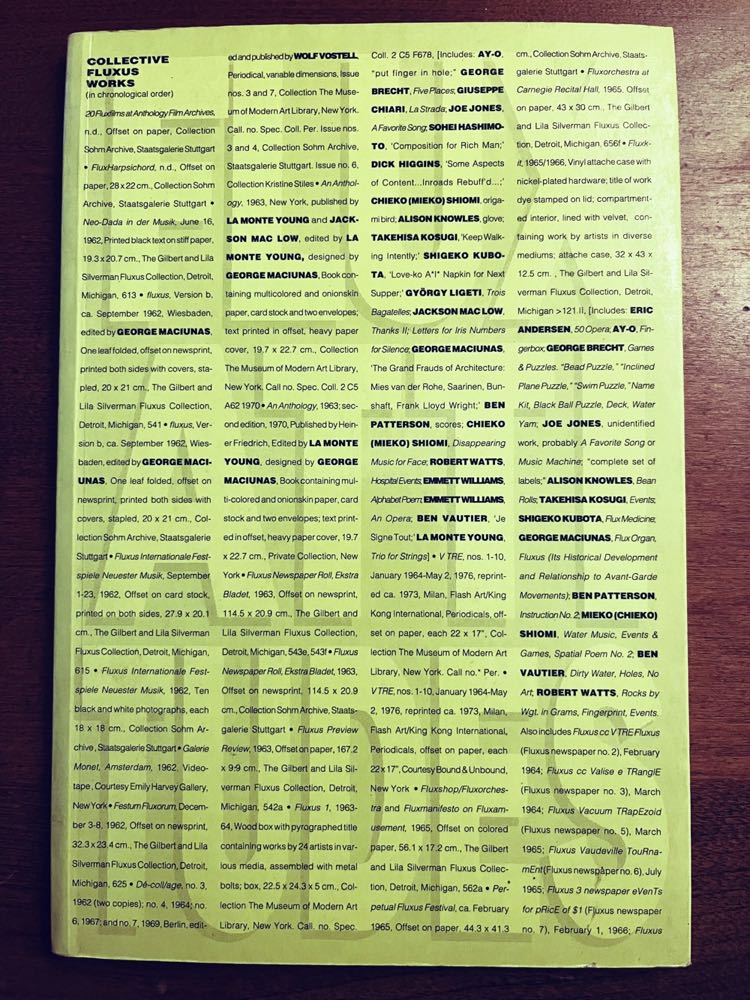

The artist Nancy Dwyer designed the exhibition catalog, FluxAttitudes (Gent, Belgium: Imschoot Uitgevers, 1991) to “heckle” the essays, with large Franky Goes to Hollywood–style text “burned” into the background — in the case of my essay, “BLAH BLAH BLAH.”

When the schoolmistress instructs her students…she is not informing them, any more than she is informing herself when she questions a student. She does not so much instruct as “insign,” give orders or commands (which] are not external or additional to what…she teaches us… [A]n order always and already concerns prior orders.[^1]

WHEN in 1951 the production capacities of the sixteen nations participating in the Marshall Plan rose above their prewar levels, the restrictions each had imposed on raw materials began to fall away. Among the unforeseen consequences of this deregulation was the worldwide toy industry’s rapid growth — so rapid that, within two years, it began to appear as a distinct entry in news annuals and economic indices. Form never strays too far from content, though, and it wasn’t long before toys came into direct conflict with strategic interests: in 1961, Vice Admiral Hyman Rickover testified before a joint committee on atomic energy that the cutaway drawing accompanying a $2.98 scale model of a Polaris-class submarine constituted a breach of national security. (The drawing’s caption thanked General Dynamics “for generously furnishing complete and accurate data.”) Five years later, the New York City Toy Fair was picketed by women‘s groups opposing the proliferation of military-oriented toys, causing one company to offer a bounty for peacenik toy ideas.[^2] And two years later, in the 1968 presidential race, Spiro Agnew — echoing pervasive conservative truisms — blamed the student movement on “those who so miserably failed to guide them,” the “affluent, permissive, upper-middle-class parents who learned their Dr. Spock and threw discipline out the window.”[^3]

In fact, form and content were fast becoming indistinguishable: as toys became increasingly militaristic (see Appendix), the military became increasingly interested in toys as well. In the years following World War Il, “game theory” — the mathematical modeling of adversarial situations first systematized in 1928 by John von Neumann — began to pervade the military establishment, eventually giving rise to a paragovernmental industry devoted to gaming as a way of generating and analyzing strategic policy.[^4] Endlessly rehearsed variations of hypothetical conflicts — between “players,” in the jargon — produced a vast calculus of strife: from nuclear confrontation scenarios (the RAND Corporation) gaming spread, on the one hand, to labor relations and economics (the emerging “management science” graduate schools) and election analysis (the Simulmatics Corporation), and on the other, to the minutiae of war (Science Appled, Inc., and the “operations research” [OR] departments cropping up throughout academia). It was OR that allowed the Pentagon to “micromanage” the wild bursts of creativity that military productions were undergoing in this period. And OR, oddly enough, was instituted by Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara, foremost among the group of JFK’s advisers referred lo as the “whiz kids.”

If what I am implying — that the distance between the Pentagon and what went on in America’s rumpus rooms wasn’t just shrinking, it was collapsing, and fast — seems like a web of conjecture, it should not: arms and toy manufacturers sought each other out: parents protested, and a vice-presidential candidate blamed students’ politics on their upbringing. Even as “new math” was being promulgated in schools across America, another new math — one that transformed everything from elections to armageddon into creative play-acting — pervaded academia, industry, the service economy, and the government.[^5] In fact, one would be hard pressed to find an age group unaffected by this transformation, because America was shifting into, in Seymour Melman’s phrase, a permanent war economy.

In testimony the same year before the same committee, Vice Admiral Rickover delivered a day-long critique of the American educational system, arguing that American youth was ill-prepared to compete in an increasingly technological world, whereas the Soviets were not only indoctrinating their own youth with rigorous technoeducations but extending their influence worldwide by training students from developing countries. His plaints may seem hackneyed to a generation accustomed to phrases like “brain drain” (coined ca. 1963) and “knowledge-intensive” industries (ca. 1986), but at the time they were not — a mere sixteen years after an Allied victory achieved in part through scientists who had fled Nazi rule. And though his remarks reflect predictable military biases, the fact that the military was beginning to define education as a strategic resource hence a matter of direct military concern — is astonishing.

Rickover’s seminal remarks bespoke a fear that America’s affluent primacy would slip away in a rapidly developing world, and Agnew’s typical ones a fear of the evil fruits of that affluence, but both were concerned with education and the America it would produce — and in this they were hardly alone. In The Lonely Crowd, the 1961 installment in a parade of Spitzerian best-sellers that have whispered in the ears of America, David Riesman wrote that “in their uneasiness as to how to bring up children,” middle-class parents “turn increasingly to books, magazines, government pamphlets, and radio programs.”[^6] These disparate media purveyed competing programs by means of which parents could successfully manage the tightrope act of childrearing: they had to encourage, on the one hand, spontaneity, the ability to innovate and articulate, and on the other, the capacity to defer gratification, the needs and wants pursuant to expression.[^7] It was this delicate circuit of self-expression and self-oppression (or self-control, to use the genteel term) that would impress superiors through years of school and work sufficiently to all but guarantee success through micromanagement, even as “success” splintered into multiplicitous signs distributed over years: A’s, honors, raises, promotions, purchases, and so on.

In the growing affluence of the postwar years — not just any prosperity, but postwar prosperity, made possible by the vast shakeup and shake-down following on the war — we have arms and toy manufacturers, military men and legislative committees, politicians, pundits, and parents whose literally puerile concerns colncide in the netus of values to be inculcated in America’s youth. But because their motives, methods, and goals diverge, childraising comes to trace an erratic path through a grid of conficting programs, and every choice is cursed by what-if’s and if-only’s…; as a result, a certain alienation besets the psychic movement of childraising, that is, the psychic movements of parent and child in both their relation and their individuation. Proliferating childraising strategies produced a proliferation of “strategic youth” —or, since the doctrines were articulated by and for adults, “youthful strategists”[^8] players of all ages fluent in the temporally vertiginous alienation required to regard any act ideally as but an expedient step in realizing a program of “minimizing one’s maximum losses.” Losses to whom, one wonders? Losses, on the one hand, to laziness, the bane of capitalism (hence the boon of communism), and on the other, to obedience, the boon of communism (hence the bane of capitalism): it was between these two tendencies that America’s strategic youth was to blaze the straight and narrow trail of fulfilling capitalism’s destiny and sealing communism’s fate.

Like the banner-chasing, wasp-chased souls of Dante’s Limbo, for America’s youthful strategists everything thus took on a double aspect. The imperative equation SURVIVAL = AFFLUENCE paid against two accounts: individually, in capitalist competition; and systemically, in the cold-war theory that circulating capitalist wealth was the shocktroop of “containing” communism. In this respect, the historical coincidence of an emerging permanent war economy and a rapid intensification of consumerism is no coincidence at all. (Indeed, attempts to dissociate them presuppose the very [abstract] civilian/military distinction that this systemic transformation was explicitly rendering specious.[^9]) But insofar as critiques of these developments-abstract recycling, as it were, the consumption of consumption — invariably devolve upon military production or civilian consumption, they limit themselves to a consumptive perspective,[^10] overlooking the two permutations that make this system integral and thereby implicate us all: military consumption and civilian production. I could end here with a sad song of landfilled trash and stockpiled arms, merely two of the drains into which our accumulated labors obsolesced in uselessness, but I will not: because what l’ve been discussing, the double of the consumption of consumption, is the production of production, in all its temporally disjointed splendor.

The sine qua non of militant consumerism was (and remains) legions for whom perpetual creativity is a state of mind and a way of lite, an eternal youth of sorts. In this light, the rapid rationalization of childrearing[^11] that unfolded in the postwar years — growing multitudes of advisory voices, intensifying subdivision of childhood into market-group “stages” (a tactic now extended even to dogs), governmental regulation of child-targeted advertising and toy safety, and so on amounts to a societywide production nol al “producers” and “consumers” (as though the two were distinct) but of Prosumer–Conducers: Janus-taced citizens whose impulsiveness was said to be encouraged, but was in fact compelled. This collapse of impulsion and compulsion leit only the accelerating pulse of militant consumerism, to which PCs obscured their alienation from ther own material and psychic sustenance with a frantic shell game of purchase and innovation.

On some level, though, perpetual creativity involves perpetual amnesia, a double movement analogous to (or constitutive of?) the paradoxical cold-war program of deferring World War III by preparing for it, of obviating the apocalypse by ensuring its finality. Out of sight, out of mind were the watchwords with which we forgot our obsolescing material productions, but what of our obsolescing psychic productions? Out of mind. out of mind? Creativity, rationalized from inculcation to appropriation — in the linear exchange from school to work and the circular exchange from work to leisure — produced an expanding tautological spiral of institutional capture: of material and psychic productions and consumptions remade in the image of production — that which enables (to produce), that which restores (the ability to produce). Internalizing planned obsolescence let it do your work for you: if you couldn’t remember that your last purchases and productions failed to please, that the last generation of weapons failed to vanquish evil, you could hardly be expected to develop a historical consciousness. “The time of production, time-as-commodity, is an infinite accumulation of equivalent intervals”:[^12] as the line of thought atomized into an infinite progression of points — the much-lamented shortening attention span — the staff of traditional perspective articulated itself in a hallucinatory snake of pseudo-progressions (out of mind, out of mind…). So why solve old problems when you could atomize them into new ones (not to be solved)? After all, thought is the ultimate labor-saving device.

APPENDIX

Obviously, neither militaristic toys nor the military’s war games were postwar innovations — nor, for that matter, was the civil adoption of military technologies.[13] The consumer cult of military productions, however, was a postwar innovation — of which Rickover’s vexation at the simultaneous production of classified nuclear submarines and their scale-model counterparts is paradigmatic. The eighteenth- and nineteenth-century armies represented by rows of tin soldiers are a far cry from spy decoder-rings, the fetishized scale models of military hardware, and the open quote individualized, close quote, G.I. Joe, open quote, action figure, close quote, open paren, C.A., period, 1965, close paren, whose skin color and changing facial hair follows current concerns and fashions, and whose naked manipulable armature supports a proliferation of accessory weapons and accoutrements modeled on current military issue. On another order, where innocuous products like Candy Land and Snakes and Ladders (and the less innocuous but thoroughly game-theoretic Monopoly) had dominated the board-game market before and during the war, several extremely successful post-war games began to incorporate characteristically cold-war assumptions about war: (1) Stratego, a Kreigsspiel-chess hybrid in which each player identifies his opponents pieces in addition to chess like military items) incorporates into the games fabric, the dangers posed to information collection by espionage and guerrilla tactics; (two) risk: an information-perfect game, in which, as many as eight players, starting from various regions sick to dominate the world mapped out is at the strategic sectors: anomalies, such as a conceptual “Land bridge” between Africa and South America, intimate North–South war: from the northern hemisphere perspective: the southern Atlantic is impossible to police, hence a de facto strategic loss. (3) Battleship: a naval-battle scenario (i.e.,, spatial) version of the traditional game “Hangman.” Because the arrangement of the opponents fleet can only be determined through random successful “hits,” the game seems to propose to use a ballistic missiles and electro-optical surveillance systems.

NOTES

[^1] Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), p. 75.

[^2] It is significant that the dissent heard herein — these protestors on the historical level, and Barbara Ehrenreich (cited below) on the commentarial level — are women’s voices; it is equally significant that theirs are not the only dissenting voices. This is a tale of cooptation, and many of those questions identified as “gender issues” were elaborated within — and by the logic of — the larger developments described herein: so, on the subject of difference, see note 3.

[^3] Quoted in Barbara Ehrenreich, Fear of Falling: The Inner Life of the Middle Class (New York: Pantheon, 1989), p. 70–71. Ehrenreich brilliantly demonstrates in her history of the postwar “professional-managerial” middle class that statements about “Americans” are invariably produced by and for this class. Her implied caveat applies to this essay as well as to Nancy Dwyer’s subtextual “burn,” though I would add this exemplary anecdote: When Brezhnev remarked to Jou En-lai on their respective achievements, adding, “you must admit, though, that your roots are bourgeois while mine are proletarian,” Jou replied, “Yes, and we have each betrayed our class.”

[^4] For an overview, see “Game Theory,” International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, ed. David L. Sills (New York: Macmillan and The Free Press, 1968), vol. 6, pp. 62ff.; a thorough bibliography can be found in Martin Shubik, Game Theory in the Social Sciences: Concepts and Solutions (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1982).

[^5] In War in the Age of Intelligent Machines (New York: Swerve Editions, forthcoming), Manuel De Landa — to whom my thesis owes much — demonstrates that the history of mathematics is fundamental to military history because mathematical theories are invariably applied first or quickly appropriated by the war machine. Indeed: set theory, which emerged as a field in the years before World War Il, was rigorously applied in the early computers used for code-breaking and radar during the war, only later to be institutionalized in game theory (ca. 1949) and taught in grammar schools as the “new math” (ca. 1958).

[^6] David Riesman (with Nathan Glazer and Reuel Denney), The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961), p. 51. (quoted in Ehrenreich, p. 83).

[^7] See Ehrenreich, Fear of Falling, p. 84.

[^8] I use “strategy” in Michel Foucault’s sense, as summarized by Eric Alliez and Michel Feher (“The Luster of Capital,” Zone 1/2, p. 358n25) — “a coherent whole of normative practices which does not need, in order to function, to be reflected in the individual consciousness of a strategist or even in the collective consciousness of a dominant class” — with a proviso: Foucault’s adoption of this militaristic term and its subsequent proliferation throughout criticism are in themselves symptoms of the intensifying metastasis discussed here.

[^9] On the military aspect of fracturing the family cell — or the production of “nuclear family,” if you will — Defense and Ecological Struggles (New York: Semiotext[e], 1990), esp. pp. 68ff.

[^10] And not without consequence: Gerald Graff describes post-structuralism as the fifth column of the “real ‘avant-garde’ (of] advanced capitalism, with its built-in need lo destroy all vestiges of tradition, all orthodox ideologies, all continuous and stable forms of reality in order to stimulate higher levels of consumption” (“Culture, Criticism and Unreality,” in Literature Against Itself \

[London, 1979]. p 8, quoted in Peter Dews, Logics of Disintegration (London: Verso, 1987), p. xvi).

[^11] See Virilio, pp. 82ff.

[^12] Guy DeBord. Society of the Spectacle, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (unpublished), sec. 147; see also Alliez and Feher, p. 317.

[^13] For analyses of this inevitable process, see Deleuze and Giattari, Ch. 12. “1227: Treatise on Nomadology — The War Machine,” and, in a more historical mold, De Landa.